From "Of the Dustmen of London"

London Labour and the London Poor

Henry Mayhew

Dust and rubbish accumulate in houses from a variety of causes, but principally from the residuum of fires, the white ash and cinders, or small fragments of unconsumed coke, giving rise to by far the greater quantity. Some notion of the vast amount of this refuse annually produced in London may be formed from the fact that the consumption of coal in the metropolis is, according to the official returns, 3,500,000 tons per annum, which is at the rate of a little more than 11 tons per house; the poorer families, it is true, do not burn more than 2 tons in the course of the year, but then many such families reside in the same house, and hence the average will appear in no way excessive. Now the ashes and cinders arising from this enormous consumption of coal would, it is evident, if allowed to lie scattered about in such a place as London, render ere long, not only the back streets, but even the important thoroughfares, filthy and impassable. Upon the Officers of the various parishes, therefore, has devolved the duty of seeing that the refuse of the fuel consumed throughout London is removed almost as fast as produced; this they do by entering into an agreement for the clearance of the "dust-bins" of the parishioners as often as required, with some person who possesses all necessary appliances for the purpose -- such as horses, carts, baskets, and shovels, together with a plot of waste ground whereon to deposit the refuse. The persons with whom this agreement is made are called "dust-contractors," and are generally men of considerable wealth...

These dust-contractors are likewise the contractors for the cleansing of the streets, except where that duty is performed by the Street-Orderlies; they are also the persons who undertake the emptying of the cesspools in their neighbourhood; the latter operation, however, is effected by an arrangement between themselves and the landlords of the premises, and forms no part of their parochial contracts...

The dust thus collected is used for two purposes, (1) as a manure for land of a peculiar quality; and (2) for making bricks. The fine portion of the house-dust called "soil," and separated from the "brieze," or coarser portion, by sifting, is found to be peculiarly fitted for what is called breaking up a marshy heathy soil at its first cultivation, owing not only to the dry nature of the dust, but to its possessing in an eminent degree a highly separating quality, almost, if not quite, equal to sand...The finer dust is also used to mix with the clay for making bricks, and barge-loads are continually shipped off for this purpose.

The dust-yards, or places where the dust is collected and sifted, are generally situated in the suburbs, and they may be found all round London, sometimes occupying open spaces adjoining back streets and lanes, and surrounded by the low mean houses of the poor; frequently, however, they cover a large extent of ground in the fields, and there the dust is piled up to a great height in a conical heap, and having much the appearance of a volcanic mountain. The reason why the dust-heaps are confined principally to the suburbs is, that more space is to be found in the outskirts than in a thickly-peopled and central locality...

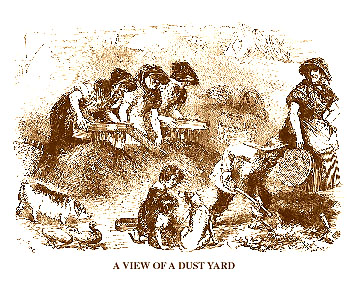

A visit to any of the large metropolitan dust-yards is far from uninteresting. Near the centre of the yard rises the highest heap, composed of what is called the "soil," or finer portion of the dust used for manure. Around this heap are numerous lesser heaps, consisting of the mixed dust and rubbish carted in and shot down previous to sifting. Among these heaps are many women and old men with sieves made of iron, all busily engaged in separating the "brieze" from the "soil." There is likewise another large heap in some other part of the yard, composed of the cinders or "brieze' waiting to be shipped off to the brickfields. The whole yard seems alive, some sifting and others shovelling the sifted soil on to the heap, while every now and then the dust-carts return to discharge their loads, and proceed again on their rounds for a fresh supply. Cocks and hens keep up a continual scratching and cackling among the heaps, and numerous pigs seem to find great delight in rooting incessantly about after the garbage and offal collected from the houses and markets.

A visit to any of the large metropolitan dust-yards is far from uninteresting. Near the centre of the yard rises the highest heap, composed of what is called the "soil," or finer portion of the dust used for manure. Around this heap are numerous lesser heaps, consisting of the mixed dust and rubbish carted in and shot down previous to sifting. Among these heaps are many women and old men with sieves made of iron, all busily engaged in separating the "brieze" from the "soil." There is likewise another large heap in some other part of the yard, composed of the cinders or "brieze' waiting to be shipped off to the brickfields. The whole yard seems alive, some sifting and others shovelling the sifted soil on to the heap, while every now and then the dust-carts return to discharge their loads, and proceed again on their rounds for a fresh supply. Cocks and hens keep up a continual scratching and cackling among the heaps, and numerous pigs seem to find great delight in rooting incessantly about after the garbage and offal collected from the houses and markets.

In a dust-yard lately visited the sifters formed a curious sight; they were almost up to their middle in dust, ranged in a semi-circle in front of what part of the heap which was being "worked;" each had before her a small mound of soil which had fallen through her sieve and formed a sort of embankment, behind which she stood. The appearance of the entire group at their work was most peculiar. Their coarse dirty cotton gowns were tucked up behind them, their arms were bared above their elbows, their black bonnets crushed and battered like those of fish-women; over their gowns they wore a strong leathern apron, extending from their necks to the extremities of their petticoats, while over this, again, was another leathern apron, shorter, thickly padded, and fastened by a stout string or strap round the waist. In the process of their work they pushed the sieve from them and drew it back again with apparent violence, striking it against the outer leathern apron with such force that it produced each time a hollow sound, like a blow on the tenor drum. All the women present were middle aged, with the exception of one who was very old -- 68 years of age she told me -- and had been at the business from a girl. She was the daughter of a dustman, the wife, or woman of a dustman, and the mother of several young dustmen -- sons and grandsons -- all at work at the dust-yards at the east end of the metropolis....

The dustmen are, generally speaking, an hereditary race; when children they are reared in the dust-yard, and are habituated to the work gradually as they grow up, after which, almost as a natural consequence, they follow the business for the remainder of their lives. These may be said to be born-and-bred dustmen. The numbers of the regular men are, however, from time to time recruited from the ranks of the many ill-paid labourers with which London abounds...

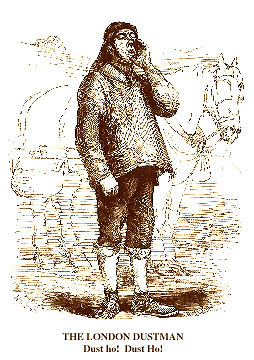

The manner in which the dust is collected is very simple. The "filler" and the "carrier" perambulate the streets with a heavily-built high box cart, which is mostly coated with a thick crust of filth, and drawn by a clumsy-looking horse. These men used, before the passing of the late Street Act, to ring a dull-sounding bell so as to give notice to housekeepers of their approach, but now they merely cry, in a hoarse unmusical voice, "Dust oy-eh!" Two men accompany the cart, which is furnished with a short ladder and two shovels and baskets. These baskets one of the men fills from the dust-bin, and then helps them alternately, as fast as they are filled, upon the shoulder of the other man, who carries them one by one to the cart, which is placed immediately alongside the pavement in front of the house where they are at work. The carrier mounts up the side of the cart by means of the ladder, discharges into it the contents of the basket on his shoulder, and then returns below for the other basket which his mate has filled for him in the interim. This process is pursued till all is cleared away, and repeated at different houses till the cart is fully loaded; then the men make the best of their way to the dust-yard, where they shoot the contents of the cart on to the heap, and again proceed on their regular rounds.

The manner in which the dust is collected is very simple. The "filler" and the "carrier" perambulate the streets with a heavily-built high box cart, which is mostly coated with a thick crust of filth, and drawn by a clumsy-looking horse. These men used, before the passing of the late Street Act, to ring a dull-sounding bell so as to give notice to housekeepers of their approach, but now they merely cry, in a hoarse unmusical voice, "Dust oy-eh!" Two men accompany the cart, which is furnished with a short ladder and two shovels and baskets. These baskets one of the men fills from the dust-bin, and then helps them alternately, as fast as they are filled, upon the shoulder of the other man, who carries them one by one to the cart, which is placed immediately alongside the pavement in front of the house where they are at work. The carrier mounts up the side of the cart by means of the ladder, discharges into it the contents of the basket on his shoulder, and then returns below for the other basket which his mate has filled for him in the interim. This process is pursued till all is cleared away, and repeated at different houses till the cart is fully loaded; then the men make the best of their way to the dust-yard, where they shoot the contents of the cart on to the heap, and again proceed on their regular rounds.

The dustmen, in their appearance, very much resemble the waggoners of the coal-merchants. They generally wear knee-breeches, with ancle [sic] boots or gaiters, short dirty smockfrocks or coarse gray jackets, and fantail hats. In one particular, however, they are at first sight distinguishable from the coal merchants' men, for the latter are invariably black from coal dust, while the dust-men, on the contrary, are gray with ashes.

Note: This excerpt represents only a fraction of Mayhew's original observations. The editors urge those who are interested to consult the full text, "Of the Dustmen of London," which can be found in Volume II of Mayhew's massive 1851-2 survey, London Labour and the London Poor.