Seeing Double: Jewish Isolation in

Oliver Twist and Our Mutual Friend

Murray Baumgarten

The Dickens Project

University of California, Santa Cruz

The Jew, Fagin, in Charles Dickens' Oliver Twist (1838) stands alone; he has no double. (While mention is made of a fellow Jew [Barney], he plays no role in the dramatic action of the novel.) Though an argument might be made to link Fagin with Oliver, the narrative logic of the novel works to deny the connection. Instead of seeing Fagin, like Oliver, as the outsider -- his Jewishness placing him at even more of a disadvantage than Oliver's orphaned status, and suggesting that both characters echo each other in asking for more -- Oliver and Fagin are placed in opposition, so that for the former to claim his rightful place in society the latter must die.

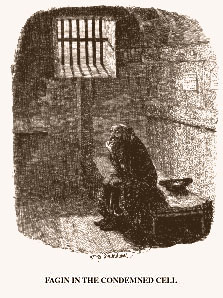

Dickens' s text and Cruikshank's illustrations reinforce each other. As J. Hillis Miller notes, "The relationship between text and illustration is clearly reciprocal. Each refers to the other. Each illustrates the other, in a continual back and forth movement which is incarnated in the experience of the reader as his eyes move from words to picture and back again, juxtaposing the two in a mutual establishment of meaning" [1]. Consider then the iconic illustration, generally acknowedged as one of Cruikshank's greatest pictures, inserted in apposition to Oliver's visit to the condemned Fagin in his cell. At this point in the fiction, the devil-Jew is crazed, muttering and incoherent, and caught in the same circle of insanity that besets Sikes before he slips and hangs himself in an apparent suicide-death. Yet unlike Bill Sikes running from the hue and cry, Fagin in his prison cell is alert enough to bargain with Brownlow and Oliver for his life. Revealing where the papers attesting to Oliver's birthright are, he thinks to get him to help in an escape attempt.

Dickens' s text and Cruikshank's illustrations reinforce each other. As J. Hillis Miller notes, "The relationship between text and illustration is clearly reciprocal. Each refers to the other. Each illustrates the other, in a continual back and forth movement which is incarnated in the experience of the reader as his eyes move from words to picture and back again, juxtaposing the two in a mutual establishment of meaning" [1]. Consider then the iconic illustration, generally acknowedged as one of Cruikshank's greatest pictures, inserted in apposition to Oliver's visit to the condemned Fagin in his cell. At this point in the fiction, the devil-Jew is crazed, muttering and incoherent, and caught in the same circle of insanity that besets Sikes before he slips and hangs himself in an apparent suicide-death. Yet unlike Bill Sikes running from the hue and cry, Fagin in his prison cell is alert enough to bargain with Brownlow and Oliver for his life. Revealing where the papers attesting to Oliver's birthright are, he thinks to get him to help in an escape attempt.

Oliver offers to say a prayer for Fagin, and urges him to join. "Say only one, upon your knees, with me, and we will talk till morning." But Fagin the Jew is impervious to these Christian entreaties just as he has earlier rejected the appeal of his compatriots: "If I hoped we could recall him to a sense of his position-" Mr Brownlow notes. "Nothing will do that sir," replies the turnkey. "You had better leave him." Christian love has no taker here. Instead, as "the door of the cell opened, and the attendants returned," Fagin clutches Oliver, certain he can help him to negotiate even this gauntlet. "Press on, press on," cries Fagin. "Softly, but not so slow. Faster, faster!" Only main force holds Fagin back.

By contrast with Fagin's inability - or is it the wilful Jew's refusal?- to understand what is about to happen, the chapter ends with Oliver's participation in the narrator's meditation on death.

It was some time before they left the prison. Oliver nearly swooned after this frightful scene, and was so weak that for an hour or more, he had not the strength to walk.

Day was dawning when they again emerged. A great multitude had already assembled; the windows were filled with people, smoking and playing cards to beguile the time; the crowd were pushing, quarreling, joking. Everything told of life and animation, but one dark cluster of objects in the centre of all - the black stage, the cross-beam, the rope, and all the hideous apparatus of death.

"No Escape" the running head of this page proclaims. Not only life but even the incipient gesture of remorse that seemed to have animated Sikes at the last moment is absent. This character is unredeemable. Where others have a soul, he has an absence.

The Cruikshank figure is again instructive. In its isolation in the cell, in its presentation of Fagin as Jew-Devil stuck without maneuvering room in the condemned prisoner's cell, the stylized caricature proclaims one signal: evil will now be banished from this realm. In contrast to Cruikshank"s illustrations of Oliver's progress which, as Anthony Burton notes, recount the narrative "by composing the figures in his designs so that certain patterns of grouping and gesture recur," Fagin in his cell "ironically" sits "beneath a barred window" which "admits only the peaceful light of day and no danger from outside, for Fagin, heedless of the light, has evil deep within him" [2]. In terms of the novel's plot Fagin now bears the burden not only of his own criminal behavior but the villainy of Monks, Oliver's half-brother. He has become the Jew as scapegoat.

Ironically, Dickens' effort to locate Fagin as scapegoat has an implicit boomerang effect. When Christian tradition makes Jesus the ultimate scapegoat for humanity, dying for the sins of the human race, it brings him forward from the subtext to the center of the action. The only way to avoid this boomerang effect is to cordon Fagin off and separate him in all possible ways from Oliver, who has played the Christian scapegoat's role prior to this moment. This also accounts for the uneasiness which many readers have felt at Fagin's sentence and the sentimentality of the concluding passages of this chapter's meditations on death.

Even more surprising is the impact of isolating Fagin, the Jew. When, as Jonathan Grossman notes, Oliver calls Fagin "The Jew! The Jew! at the beginning of chapter 35, he not only "naturalizes his position in the middle class, with Mr. Brownlow, who also later privileges the term 'the Jew' over Fagin's name" [3], he is also severing any link that might have existed between them. In a novel of doublings and splittings so full as to be representative of Dickens's fictional world-making, this epithet ensures that Fagin is alone.

Thus unlike the other characters in the novel, his is a life that is unsayable and unnarratable. His existence is ontologically different in kind from that of the other characters, despite the ongoing process of secularization of Christian myth that helps to articulate Oliver as the child-innocent speaking the Queen's English. The heteroglossic world of the Artful Dodger or Nancy does not extend to Fagin. His language of ingratiation, including the "My dear" and "deary" is not theirs, just as the thieves argot linked to Ikey Solomons and the marginal world of fences and old-clothes-dealers does not mark him for example as part of Mayhew's sociological explorations. When he includes Jews as members of the criminal underworld Mayhew the journalist does not use a stereotyped caricature of a Jew to illustrate and clinch his point [4]. Mayhew's description of Jewish life in the London streets is an ethnographic account. The racial epithets in his account are not his but the reported conversation of observers and apparently biased individuals. Furthermore, he notes that the supposed criminality of the Jews is untrue. The picture of the Jew as Old-Clothes Man is not a devilish, isolated figure but that of one of the London street-people going about his daily business. By contrast in Dickens's world and Cruikshank's vision, Fagin is not one of a group or class, not martyr or victim, but Mephistophelean tempter of Christians.

Thus unlike the other characters in the novel, his is a life that is unsayable and unnarratable. His existence is ontologically different in kind from that of the other characters, despite the ongoing process of secularization of Christian myth that helps to articulate Oliver as the child-innocent speaking the Queen's English. The heteroglossic world of the Artful Dodger or Nancy does not extend to Fagin. His language of ingratiation, including the "My dear" and "deary" is not theirs, just as the thieves argot linked to Ikey Solomons and the marginal world of fences and old-clothes-dealers does not mark him for example as part of Mayhew's sociological explorations. When he includes Jews as members of the criminal underworld Mayhew the journalist does not use a stereotyped caricature of a Jew to illustrate and clinch his point [4]. Mayhew's description of Jewish life in the London streets is an ethnographic account. The racial epithets in his account are not his but the reported conversation of observers and apparently biased individuals. Furthermore, he notes that the supposed criminality of the Jews is untrue. The picture of the Jew as Old-Clothes Man is not a devilish, isolated figure but that of one of the London street-people going about his daily business. By contrast in Dickens's world and Cruikshank's vision, Fagin is not one of a group or class, not martyr or victim, but Mephistophelean tempter of Christians.

Existing outside the Dickensian world of doubling and splitting, Fagin is an anomaly. The impact of his isolation depends on the ways in which every other character in the novel is part of a group. Current discussions of typologies offer a clue to the central meanings of this isolation. Much in evidence among contemporary visual artists, typologies are ways of grouping situations through repetition and variation. The detail of an individual image is framed as part of an implicit discourse, thereby making single moments part of a syntax of many. "A typology is a collection of members of a common class or type. Like natural scientists, who assemble taxonomies of living things based on genus and species, the photographers in this exhibition seek to document, in a consistent manner, examples of a specific type of subject matter for the purpose of comparison. The work is only fully effective when viewed as a suite of images, allowing the dialectic between the class and the specific member of the class to become apparent." We see "differently when [the] affinities" of one photograph "are explored in a group" linking it "to urban spaces worldwide" [5]. As part of a suite, each member in the typology can now be narratable; each is part of a discourse. It is worth noting that this contemporary artistic habit echoes strategies at work in Dickens's era, deployed by scientists like Lyell, Babbage, and Faraday, and that led in Darwin's hands to revolutionary transformations of world-view and social understanding.

Note also how the impact of these city scenes in the typological structure makes them akin to streets whose functions are inextricable from the urban whole. The analogy to Dickens's urban art is apt: in typologies single figures make visible the mechanical reproduction of repetition in fiction and in city-building. We have entered the world articulated by Walter Benjamin's analysis. The structures of repetition elaborate the movement of narration and demystify uniqueness, be it of single image or romantic godike art-creator. In this city-as-totality, urban repetitions of character, scene, and situation orient the one as part of the discourse of the many; the fiction of juxtaposition of opposites defines the assemblage of possible meanings.

In this changing, shifting world, to leave one figure dangling without doubling is to stereotype him and make him available as the screen for the Rorschach projection of all that is to be excluded. Like Malvolio he is the enemy of the revels and must be imprisoned, and even banished, for the feasting and festivities to come into their own. To place the Jew outside this city discourse, as Dickens does, is to stereotype him as the incarnation of evil, and articulate a literary economy of anti-semitism, thus preparing the way for the racialist representations that defined general cultural images of the Jews for better than a hundred years of English and European culture from the publication of Oliver Twist in 1838. It is also to understand the continuities of that image of the Jew with the more religiously rooted anti-semitic tradition of medieval, Crusader, and Renaissance productions, including Barabbas and Shylock.

It is no surprise then to read contemporary Jewish responses in which praise of the generosity of Dickens's fictional sympathies leads to a complaint that is registered as a request: is it possible for the Jew now formally emancipated to find a different cultural representation? Can someone in the century and cultural tradition that prided itself on the ability to give the unspoken masses voice and tell the stories of those so long deemed unworthy of having them - think only of Carlyle and the Chartists, Dickens and the homeless, Arnold and Wragg, the abandoned widow - also strike off a fictional world that will tell the story of the Jews as something other than victims or demons? This is the burden of the query of the Jewish Chronicle in 1854, asking "why Jews alone should be excluded from 'the sympathizing heart' of this great author and powerful friend of the oppressed." In his reply to an invitation to attend the anniversary dinner of the Westminster Jewish Free School Dickens pleaded innocence: "I know of no reason the Jews can have for regarding me as 'inimical' to them," citing the "sympathetic way in which he had treated the persecution of the Jews" in his Child's History of England in 1851. Choosing to ignore the evidence of Fagin, he noted that "on the contrary . . . I believe I do my part toward the assertion of their civil and religious liberty, and in my Child's History of England I have expressed a strong abhorrence of their persecution in old time." Arguing against religiously based anti-semitism, Dickens emphasizes his championing of the rights of English subjects whatever their religious beliefs. The terms in which he phrases his stalwart repudiation of religiously based anti-semitism locate him in his historical moment. Clear and forthright, Dickens's phrasing nevertheless indicates his lack of awareness of the growing impact phrenology was to have on the formation of a racialist rhetoric. We cannot fault him for being only a writer not a prophet; rather, we need to recover the moment of his understanding of the situation of the Jews - at the moment when it is about to become that Jewish problem so poisonously defined by the racialist rhetoric of the later nineteenth and twentieth century ideologues.

A more personal appeal led to a different and fuller response. When Eliza Davis, "who, with her husband James, a banker, had bought Dickens's London home, Tavistock House, three years earlier," wrote him about Fagin, her questions and urgings are credited with his invention of the Jewish character, Riah, in the last novel he lived to complete, Our Mutual Friend (1864). As Deborah Heller notes, "the Davises were Jewish, and . . . Mrs Davis gave voice to the distress of Dickens's Jewish readership: 'It has been said that Charles Dickens, the large-hearted, whose works plead so eloquently and so nobly for the oppressed of this country . . . has encouraged a vile prejudice against the despised Hebrew . . . Fagin I fear admits only of one interpretation: but (while) Charles Dickens lives the author can justify himself or atone for a great wrong.'" The evasions of Dickens's response are aptly underlined by Heller's analysis [6]. For my purposes what is appropriate is to rephrase the queries of the Jewish Chronicle and Mrs Eliza Davis: can the remarkable heteroglossia of the Victorian and nineteenth century novel extend its linguistic and generic resources to those not only excluded but defined by previous religiously-based habits as the to-be-banished? Or are the Jews to be inscribed and ever re-inscribed into the role of scapegoat of this imperial racialist thrust of Western culture? the first and continuing victims of its orientalism?

What is at stake here is whether the story of the Jews is possible within this secular discourse of the novel. The question leads us perforce to a discussion of Riah and the role he plays in Our Mutual Friend, and then to other Victorian novels and novelists. It is revealed in the phrasing Dickens used in his defense. The referential argument that Jews were criminals in the nineteenth century has been demolished in its own historical terms by many critics, Harry Stone and Edgar Rosenberg among them, while the issue of novelistic rights - "the assertion of their civil and religious liberty" by the Jews - though touched on by Heller deserves further elaboration. To put it another way, is the story of Riah, whose name means friend in Hebrew, narratable in the same discourse as the one that recounts the adventures of Lizzie and Charlie, Eugene and Mortimer, Bradley Headstone and Rogue Riderhood, Wegg and Venus and Sloppy?

The argument made both by the Jewish Chronicle and Mrs. Davis centers on how Fagin is not just a representation of one Jew but bears the weight of all. In his letter responding to Mrs. Davis, Dickens claims that Fagin like the Christian characters is but one of many, an assertion belied by the absence of any other Jews in the novel. Furthermore, Dickens does not engage the ways in which Mrs. Davis and the Jewish Chronicle speak out of the concerns not only of any immigrant group seeking entry into a caste society rethinking itself as a class society - with some few hedged-in limited and conditioned yet actual points of entry for newcomers - but as representatives of a people for whom individual achievement, given the conditions of their political and social subjection in diaspora/exile, meant inevitable abandonment of a people's heritage. In other words, can Riah play a role in a world that damns him for being one of the Jews and that might at best sneer at him with faint praise for any single acts of individual merit? The inquiry reveals its own result: in this world of doublings and splittings, to keep Riah separate, to make him the only Jew, is to scapegoat him as a Jew, whatever benefit results from particular actions he takes. In other words, it is not just exclusion and absence that is ideologically motivated but also singularity and non-comparability. It is a version of that French motto coined at Emancipation: "To the Jews as a nation we must grant nothing; to the Jew as an individual we must give everything," which Stanislaus de Clermont Tonnerre, a delegate from Paris to the French National Assembly responded to on December 23, 1789 by arguing that what the Jews wanted was "to be considered citizens" [7].

It is thus no surprise that for most of the novel, Riah takes the role of usurer because he is the Jew, even though by the end he is revealed as the unwilling front-man for Fledgby of Pubsey & Co. In effect, Riah acts the part of miser which Boffin only plays at being in order to teach Bella a lesson in a version of the pious fraud deriving from the theatrical traditions of the Commedia dell'arte [8]. Furthermore, the individual actions he takes, which include the central ones of sheltering Lizzie from the pursuit not only of the murderous Bradley Headstone but the libertinism of Eugene Wrayburn are situated - like the traditional Jewish garb he wears - in the gender marked axis of the novel as feminine.

Like Jenny Wren who also seeks to shelter a potential victim, in this case her father, as well as Lizzie, Riah wears skirts, a detail emphasized in text and illustration throughout the novel. And even so, he is like Fagin, the only Jew in the novel, a condition that makes him the talisman of the fictive discourse, the screen on which the absence of Christian love is projected. And in his isolation, the impossibility of any kind of Jewish story being told about him becomes manifest, for the Jew is defined via his Jewish reference group with its customs, festivals, traditions, and cultural values. Alone, Riah too is non-narratable. Even in Our Mutual Friend, the Jew is outside discourse and thus in his isolation vulnerable to caricature.

In his skirts, Riah bears the mark of his Judaism as feminization. Fagin too wears them, and there is some gender ambiguity in his first appearance when he provides food, education, and fun for Oliver. One could then argue that the power women exercise in Our Mutual Friend, from Betty Higden to Jenny Wren and Lizzie extends to him. Perhaps this is the force of that episode when Jenny and Lizzie discover that Riah is not the usurer he seems to be. Fledgby has forced him into the role (though we never discover the full particulars of the case). Once this is grasped, Jenny and Lizzie find in Riah an ally. Welcomed to their roof garden, he too can join them in "playing dead" - the only world in which they too have rights and freedoms. Thus it is appropriate that Lizzie and Jenny learn to read and write with the help of a tutor he provides, thereby gaining potential access to the rights of citizenship which they have the possible chance to exercise in the larger world of the living. What Riah learns, however, is that their hope is not his. In having agreed to serve as Fledgby's front-man, as he tells Jenny Wren,

in bending my neck to the yoke I was willing to wear, I bent the unwilling necks of the whole Jewish people. For it is not, in Christian countries with the Jews as with other peoples. Men say, "This is a bad Greek, but there are good Greeks. This is a bad Turk, but there are good Turks." Not so with the Jews. Men find the bad among us easily enough - among what people are the bad not easily found? - but they take the worst of us as samples of the best; they take the lowest of us as presentations of the highest; and they say "All Jews are alike." If, doing what I was content to do here, because I was grateful for the past and have small need of money now, I had been a Christian, I could have done it, compromising no one but my individual self. But doing it as a Jew, I could not choose but compromise the Jews of all conditions and all countries. It is a little hard upon us, but it is the truth. I would that all our people remembered it! Though I have little right to say so, seeing that it came home so late to me." (Our Mutual Friend 795 - 796)

Perhaps this is Dickens's reprise of Shylock's famous speech; but here it is not the rhetorical question of "Hath not a Jew eyes" but the self-evident answer that there is no such thing as an individual Jew in Christian countries. Given that condition, the best Riah can do is accept Jenny's invitation and enter their utopia in the world of "Come up and be dead."

Riah's Jewishness like Fagin's is evident in and through his body. In this world character, as John Jordan notes of Oliver Twist, "is something written or printed on the body, a textual effect like the designs and patterns printed upon nineteenth-century handkerchiefs" [9]. The reading of their bodies to which we are thus invited has no internal textual context since both are outside the fictional discourse. Both are extra-ordinary. Where Fagin is the manifest racialist caricature, Riah's is its latent obverse, the unmanned Jew. Sander Gilman has taught us to read the way in which foreground and background are reflections of the larger context, so clearly evident here: the psychic geography of Dickens's fictional world excludes the Jew and thus casts him out as available prey. His is the world of what Wolfgang Iser has called "the unsayable" and what D.A. Miller has characterized as "the unnarratable." What is abundantly clear is that in this city, the Jew has no address.

1. J. Hillis Miller, "The fiction of realism: Sketches by Boz, Oliver Twist, and Cruikshank's illustrations," Victorian Subjects, New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1990, p. 153. Also see Robert Patten, George Cruikshank's Life, Times, and Art, New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1992.

2. Anthony Burton, "Cruikshank as an Illustrator of Fiction," George Cruikshank: A Reevaluation, edited by Robert Patten, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1974, p. 127. See also Hillis Miller, op cit: "Cruikshank's illustrations are based on complex conventions which include not only modes of graphic representation, but also the stereotyped poses of melodrama and pantomime . . ." p. 158.

3. Jonathan Grossman, "The Absent Jew in Dickens," Dickens Studies Annual, in press, pp. 4 - 5. References to Dickens are to the Penguin edition; for textual issues concerning this and other editions of Dickens see Grossman, passim.

4. "Of the Street Jews," London Labour and the London Poor, by Henry Mayhew, New York: Dover, 1968, republication of Griffin, Bohn, and Company edition of 1861 - 1862, with a new introduction by John D. Rosenberg, pp. 115 - 132.

5. "Typologies: 9 Contemporary Photographers," exhibition organized by the Newport Harbor Art Museum, Newport Beach, California, shown at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Summer 1992.

6. Deborah Heller, "The Outcast as Villain and Victim: Jews in Dickens's Oliver Twist and Our Mutual Friend," Jewish Presences in English Literature, edited by Derek Cohen and Deborah Heller, Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1990, pp. 40 - 42.

7. "An Address by Stanislaus de Clermont Tonnerre, December 23, 1789," Out Of Our People's Past, edited by Walter Ackerman, New York: United Synagogue of America, 1977, p. 240.

8. See Ed Eigner, The Dickens Pantomime, Berkeley: UC Press, 1989.

9. John O. Jordan, "The Purloined Handkerchief," Dickens Studies Annual, vol 18 (1989), p. 14.